When the climate moves people: How to protect the rights of the displaced

- Susana Paola Navas

- Jul 14, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 17, 2025

As climate change intensifies, millions of people are being forced to leave their homes. While many tend to associate migration with crossing international borders, the reality is that most climate migration is internal, people moving from rural areas to cities, from coastal zones to higher ground, or from disaster-affected regions to nearby safer areas.

Yet whether migration occurs across borders or within a country, displaced individual often face similar challenges: a lack of safe and affordable housing, limited access to healthcare, few employment opportunities, and little to no legal recognition or protection of their rights. These gaps leave climate migrants vulnerable to poverty, exploitation, and social exclusion.

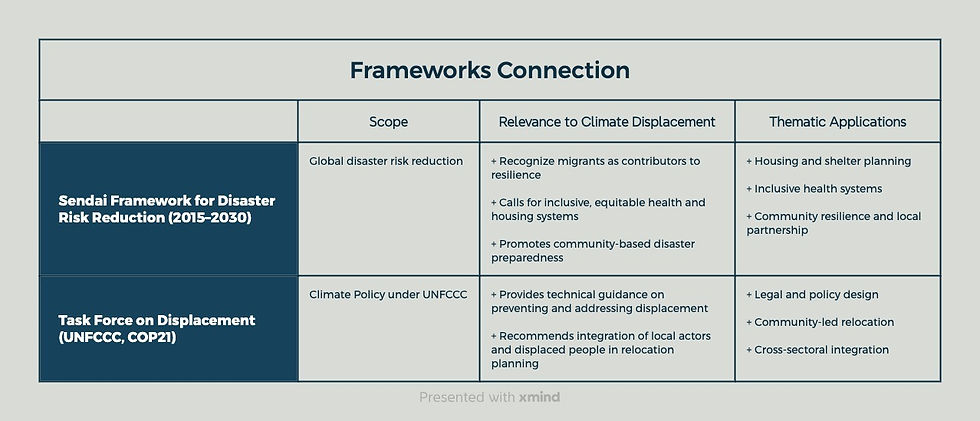

Displaced people deserved to be treated with dignity, to have equal access to basic services, and to be included in decisions that shape their lives. Global frameworks such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030) and the Task Force on Displacement under the UNFCCC offer a blueprint for inclusive, right-based, and long-term solutions. The Sendai Framework recognize migrant´s knowledge and skills as critical to disaster resilience, while the Task Force on Displacement calls for integrated policy responses to address and reduce climate-related displacement.

The sections below explore how governments and communities can put these principles into practice.

Access to housing, Healthcare, and Employment

Meeting basic needs, like housing, healthcare and employment, is the first step in restoring dignity and enabling climate migrants to rebuild their lives.

Housing is often the most urgent and visible need. When disasters like floods destroy homes or prolonged drought force rural families to abandon farmland, people are left without shelter or safe destinations. Many climate migrants end up in unsafe, overcrowded, or informal settlements that are not viable for long-term living.

Government can take concrete steps to address these needs by integrating climate displacement into urban development plans or working with communities to identify safe relocations zones. Inclusion in national housing programs as part of long-term planning is crucial. Fiji, for example, has emerged as a leader in climate-related relocation policy. Facing frequent tropical storms and rising sea levels, the government has adopted a Planned Relocation Guideline to assist vulnerable communities in moving to safer areas with adequate infrastructure. This proactive approach treats relocation not as a last resort, but as a strategy to protect citizens and build resilience. Access to health care and decent work is equally critical for both the physical and mental well-being of climate migrants. Language barriers, cultural differences, and discrimination often increase health risks and hinder access to stable employment, As a result, many migrants are pushed into unsafe, low-wage, or informal jobs with little to no legal protection.

Some countries have taken meaningful steps to address these challenges. In 2021, Colombia introduced Temporary Protection Status (TPS) for Venezuelan migrants-many of whom were fleeing both economic crisis and climate impacts. This program include work permits and vocational training, enabling migrants to access stable employment. Similarly, in Germany, the states of Berlin and Bremen have implemented policies that allow undocumented and displaced migrants to access public healthcare, without fear of deportation, through health vouchers and anonymous health cards.

Legal Protection and Inclusive Policy Design

Climate migrants need legal recognition and inclusive policies that safeguard their rights at both the national and international levels. Without legal recognition, those displaced by climate impacts often remain invisible, unsupported, and vulnerable to further harm.

A significant challenge lies in the interpretation of existing legal frameworks. The 1952 Refugee Convention does not classify individuals displaced by environmental or climate-related events as “refugees” creating legal gray areas for those crossing borders due to rising seas, drought, or extreme storms. Advocacy efforts by organizations such as UNHCR and IOM have pushed to fill this gap. While the Global Compact for Migration (2018) acknowledge environmental drivers of migration, it remains non-binding. A major development came in 2020, when the UN Human Rights Committee ruled that climate migrants cannot be returned to countries where their right to life is threatened by climate change. This precedent-setting stemmed from a case involving a man from Kiribati seeking asylum in New Zealand.

However, legal recognition is only part of the solution. Even when migrants are recognized, they may be excluded from essential services (housing, healthcare, employment) or relocated without consent or meaningful participation. Inclusive policy design must go beyond legal frameworks to ensure equity in service provision, cross-sectoral coordination, and funding and technical support. Most importantly, migrants themselves must have a voice in shaping these policies.

A notable example is Vanuatu´s National Policy on Climate Induced Displacement (2022), one of the world´s first national frameworks addressing internal displacement from climate change. The policy promotes community-led relocation and clearly states that relocation should be a last resort, undertaken only when adaptation is no longer viable.

Strengthening Community Support and Local Partnerships

Community-level action and local partnership are essential for helping climate migrants rebuild their lives while supporting host communities and strengthening social cohesion.

Displacement affect both those who move and those who receive them. Migrants often resettle in urban peripheries or rural regions with limited infrastructure and services. In many cases, local governments and civil society organizations are the first responders, offering frontline support where national systems fall short.

Local engagement is vital. Community housing initiatives, public health outreach, and education programs can help migrants integrate and respond to demographic shifts. One strong example is Bangladesh´s Community-Based Adaptation (CBA) project, where local NGOs provided resilient housing and supported women-led microenterprises in regions affected by river erosion and sea-level rise.

In the United States, the Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement Project in Louisiana relocated an entire Indigenous community impacted by coastal erosion. The project emphasized cultural preservation, community consultation and consent, and access to housing, jobs, and services, marking an important model for just and inclusive relocation.

A Human-rights-based approached is needed it to ensure climate migrant are not treated as temporary problems, but as people with rights, capabilities, and the potential to contribute to their new communities. Access to basic services is the foundation to rebuild their lives. Legal protection and inclusive policies allows migrant to be visible and include in a system meant to help them. Finally, strong communities and inclusive programs are what transform displacement into a path toward resilience and opportunity.

The following is a table summarizing the framework connections between the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030) and the Task Force on Displacement linking them to their practical application in climate-related displacement policy.

Comments